Bladder

Recurrent UTI Q&A

The bladder is the organ that sits within the bony pelvis connected to the kidneys above via the ureters and the urethra below. It is a hollow organ and acts as a reservoir for urine produced by the kidneys.

When the bladder contracts, the urine is expelled via a sphincter mechanism, down the urethra and out of the body. The outer wall of the bladder is formed by a meshwork of muscle fibres arranged in layers.

The inner wall of the bladder has a special lining called transitional epithelium, which is resistant to urine absorption.

UTI is a Urinary Tract Infection and can affect the bladder and/or the kidneys, the latter known as pyelonephritis. It is usually caused by infection affecting the bladder giving rise to the following symptoms:

- Urinary frequency with a burning sensation

- Blood in the urine, either visible or microscopic detected with Dipstix testing

- Feeling generally unwell with fatigue, high temperatures and sometimes abdominal pain

UTI is more common in women than men. As the urethra is much shorter in women than men, infection can enter the bladder from outside more easily and gain a hold causing the symptoms described above.

A common finding associated with recurrent UTI is incomplete emptying of the bladder. In women, this can be caused by the inability of the urethra to relax enough for the bladder to empty to completion: the patient often describes needing to urinate a second time very soon after going to the toilet in order to try and empty the bladder.

In men, prostate enlargement may give rise to a similar situation as the urethral passage can become obstructed often described as ‘someone stepping on a hose pipe’.

Once a UTI takes hold, it can cause an inflammatory process within the bladder wall which gives the symptoms of pain, urinary frequency and burning when passing urine.

At a microscopic level, the lining of the bladder can be damaged causing an inflammation/infection cycle that does not allow the bladder wall to repair. This can lead to the problem of ongoing or chronic infection with longterm symptoms experienced by the patient.

Patients usually consult their GP with one or more of the symptoms described.

Your doctor will take a clinical history, including any risk factors. You will be asked to provide a urine sample, which will be tested for blood cells and sent off for microscopic examination.

Your urologist may arrange an ultrasound (USS) of the renal tract to assess the kidneys and and perform a flexible cystoscopy to exclude any other causes for the symptoms within the bladder. If there any any obvious abnormalities found within the bladder, you may require a CT Urogram scan where contrast dye is given to outline the urinary system more fully (see next section).

Once you have consulted with your urologist, a number of tests may be ordered. These include one or more of the following:

- Urine tests: A number of urine tests will be used to exclude infection or abnormal cells within your urine.

- Blood tests: A number of blood tests may be ordered that will check how well your kidneys are functioning and to see if you are anaemic.

- Ultrasound (USS) of your urinary tract: This is to look at your kidneys and your bladder to see if there are any obvious abnormalities to be found. This is usually performed if there is a complicated UTI at presentation.

- KUB X-ray: KUB stands for kidney, ureter and bladder and it is a plain film to look at the urinary system and the abdomen as a whole. This plain X-ray usually reveals any obvious calcifications or stones within the urinary system that may be causing the blood in the urine.

- Flexible cystoscopy: This is a test using a small telescope to examine the urethra and bladder to check for any obvious causes of your symptoms.

- CT Urogram: This is a special type of x-ray scan whereby the urinary tract is examined again for any abnormalities. Contrast dye is usually injected into a blood vessel of the arm to outline the urinary system. Blood in the urine (haematuria) is an indication for this investigation.

The treatment of your UTI problem will be discussed with you once the initial investigations are complete.

The treatment plan is made on an individual basis once all the risks and benefits have been discussed with you:

- Lifestyle changes – keeping well hydrated, emptying the bladder after sexual intercourse, cranberry juice/tablets that can alter the acidity of the urine thereby making it more difficult for an infection to take hold.

- Long term, low dose antibiotics – this is an option for some patients with rotation of the type of antibiotics at intervals to try and prevent resistance occurring

- Short course antibiotics – this involves treating an infection with a higher (treatment) doses as it occurs.

- High dose, extended course antibiotics – this may appear counterintuitive in view of the risk of antibiotic resistance mentioned above; however, recent evidence has show this may be a good option especially in very resistant cases.

- Bladder instillation therapy – Cystistat is a naturally occurring substance that can assist in repairing the damage to the bladder that occurs during a UTI. A number of treatments are given over weeks and months and this can give excellent symptom control for the longer term. See Cystistat Bladder Therapy Q&A

- Urethral dilatation – incomplete emptying of the bladder can be a causative factor in patients with recurrent UTIs. See Urethral Dilatation Q&A

Painful Bladder Syndrome (PBS)/Interstitial Cystitis (IC) Q&A

PBS is a condition affecting mainly women in their 40’s and is relatively common (1 n 50) with some patients having symptoms from childhood. It is also known as Interstitial Cystitis (IC); however, this term should be reserved if the condition is particular severe. It is of unknown cause and can present with the following symptoms:

- Urinary frequency with a burning sensation on urination

- Vulval and/or lower abdominal pain of a chronic nature

- Feeling generally fatigued, back pain and pain during intercourse

The condition was first described in 1887 and to date, no specific cause has been found for this potentially debilitating condition. Various hypotheses have been put forward including an infective cause which damages the bladder wall, an auto-immune disease process, damage to the bladder caused by changes in the urine constituents and changes in the nerve supply to bladder.

Investigations are primarily carried out to exclude other causes of the presenting symptoms. These include:

Urine tests – to exclude infection

Cystoscopy – to exclude other problems within the bladder such as stones or tumours/growths. Previously, your urologist would take biopsies of the bladder wall to confirm specific changes at a microscopic level; however, this has fallen out of favour in recent times as there is less proof that there are any specific cellular changes in PBS/IC.

Cystometrogram (CMG)/Urodynamics – some patients with PBS/IC have a small capacity bladder with pain on filling and the CMG can confirm this and assess the functioning of the bladder, pointing to a diagnosis of PBS/IC.

The treatment of PBS/IC will be discussed with you once the investigations are complete.

The treatment plan is made on an individual basis once all the risks and benefits have been discussed with you:

Lifestyle changes – avoid foods that may irritate the bladder lining such as acidic foods, alcohol, caffeine containing foods (e.g. coffee, tea, Coca Cola, chocolate) and spicy foods. Each patient is different and so it may be a process of elimination to find what suits you best.

Reducing stress levels may also improve the situation.

Medications – these aim to combat pain and include NSAIDs, paracetamol and weak opioids. Other medications that reduce the overactivity element of the condition include tolteridine, solfenacin and mirabegron.

Bladder instillation therapy – Cystistat is a naturally occurring substance that can assist in repairing the damage to the bladder that is presumed to occur in PBS/IC. A number of treatments are given over weeks and months and this can give excellent symptom control for the longer term. See Cystistat Bladder Therapy Q&A (link)

Hydrodistension of the bladder – this is carried out under a short general anaesthetic and involves filling the bladder with saline to stretch the bladder. This sometimes good symptom relief when used in combination with some of the other options above.

Bladder Cancer Q&A

The bladder is the organ that sits within the bony pelvis connected to the kidneys above via the ureters and the urethra below. It is a hollow organ and acts as a reservoir for urine produced by the kidneys.

When the bladder contracts, the urine is expelled via a sphincter mechanism, down the urethra and out of the body. The outer wall of the bladder is formed by a meshwork of muscle fibres arranged in layers.

The inner wall of the bladder has a special lining called transitional epithelium, which is resistant to urine absorption.

Cancer develops when the cells of the body divide and reproduce in an uncontrolled manner to form a mass of tissue that can invade the surrounding organs and also spread to distant parts of the body (metastases).

The commonest type of bladder cancer is Transitional Cell Carcinoma (TCC), which arises from the inner lining of the bladder.

The majority of bladder cancers remain in this superficial lining and grow inwards towards the cavity of the bladder.

A more serious situation occurs when the cancer grows outwards into the muscle layers of the bladder and beyond invading surrounding organs and travelling to distant parts of the body (metastases).

Bladder cancer is the 5th commonest cancer in men and 10th commonest in women. In total more than 11 000 people are diagnosed with bladder cancer each year. Some known risk factors are as follows:

- Age: bladder cancer tends to affect an older age group and the average age at diagnosis is around 65.

- Sex: bladder cancer is more common in men compared to women. The ratio is around 3:1. This may be due to smoking and industrial exposure (see below).

- Cigarette smoking: smoking increases your risk of getting bladder cancer. Some of the additives in cigarettes can cause bladder cancer. The risk of developing bladder cancer if you smoke is 2-3 times higher than in people who don’t smoke.

- Occupational exposure: specific chemicals have been identified that are associated with an increased risk of developing bladder cancer. These include chemicals used in the dye and rubber industry, long-term exposure to some hair dyes and workers in the petroleum and PVC industries.

- Family history of bladder cancer: several genes have been identified as being important in the development of bladder cancer.

- Chronic bladder inflammation: if the bladder is chronically irritated (for instance, recurrent urinary tract infections, bladder stones or long term catheterisation) bladder cancer can occasionally develop. This is usually a Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) which is more common in skin cancers, again due to chronic irritation.

- Cyclophoshamide: this is used in some chemotherapy treatments and has been associated with bladder cancer.

The commonest symptom of bladder cancer is passing blood in the urine (haematuria).

This may range from a pinkish colour of the urine to an obvious deep red colour. You may experience dysuria (pain on urination). Some patients present with lower urinary tract symptoms such as frequency, urgency or nocturia.

Patients usually consult their GP with one or more of the symptoms described.

Your doctor will take a clinical history, including any risk factors. You will be asked to provide a urine sample, which will be tested for blood cells and sent off for microscopic examination.

Your doctor will examine you and this may include a rectal or vaginal examination. If there is any blood in the urine or a suspicion of bladder cancer your GP will then refer you to a urologist.

At the consultation with your urologist, the clinical history and examination will be confirmed.

Once you have consulted with your urologist, a number of tests may be ordered. These include one or more of the following:

- Urine tests: A number of urine tests will be used to exclude infection or abnormal cells within your urine.

- Blood tests: A number of blood tests may be ordered that will check how well your kidneys are functioning and to see if you are anaemic.

- Ultrasound (USS) of your urinary tract: This is to look at your kidneys and your bladder to see if there are any obvious abnormalities to be found.

- KUB X-ray: KUB stands for kidney, ureter and bladder and it is a plain film to look at the urinary system and the abdomen as a whole. This plain X-ray usually reveals any obvious calcifications or stones within the urinary system that may be causing the blood in the urine.

- Flexible cystoscopy: This is a test using a small telescope to examine the urethra and bladder to check for any obvious causes of your bleeding.

- CT Urogram: This is a special type of x-ray scan whereby the urinary tract is examined again for any abnormalities. Contrast dye is usually injected into a blood vessel of the arm to outline the urinary system.

At the time of cystoscopy you may be informed that you have a growth within the bladder. This may be a bladder cancer, however until it is examined under the microscope your urologist will not know for sure.

If necessary, a small piece of tissue can be removed at the time of cystoscopy, which can then be examined more fully. If bladder cancer is detected under the microscope you will be advised to have a rigid cystoscopy, which is carried out under general anaesthetic.

At this time, a proper assessment of the bladder cancer can be made and removal of the growth is usually performed (resection).

TURBT means Trans Urethral Resection of Bladder Tumour and is carried out under a general or spinal anaesthetic.

A rigid cystoscope is passed through the urethra into the bladder and the bladder cancer growth is removed using a small wire loop, which acts a heating element.

This enables the tumour to be removed and stops any bleeding that may occur.

If a bladder cancer has been diagnosed, your specialist will arrange a number of investigations to try and decide whether the bladder cancer is localised to the bladder or has spread beyond the bladder wall.

By knowing the stage of the disease, your urologist can decide on the best type of further management for the bladder cancer.

The staging investigations include:

- A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis

- An MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scan

- Bone scan

- Chest X-ray

The treatment of your bladder cancer will be discussed with you once the staging investigations are complete.

The treatment plan is made on an individual basis once all the risks and benefits have been discussed with you. There are many treatment options available and these include surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

Treatment can also be categorised as follows:

- Treatment for early, superficial bladder cancer

- Treatment for muscle invasive bladder cancer

75% of bladder cancers are superficial at diagnosis. They are treated by resection using the cystoscope, under general anaesthetic.

The reason for early treatment and subsequent close monitoring is to try and prevent progression of the cancer to invasive disease.

Once you have had your tumour resected, your specialist will probably advise that you have intravesical chemotherapy, which may prevent the tumours growing back. You will be advised to have regular cystoscopies, initially at three-month intervals, to make sure that there has been no return of the tumour to your bladder.

If the bladder remains clear, the intervals between checks will increase to annual flexible cystoscopy check-ups, carried out in the outpatients department.

Up to 25% of bladder cancers are invasive at diagnosis. The treatment options include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy or a combination of these.

Surgery will involve removing the entire bladder (radical cystectomy) and either forming a ileal conduit, which will allow the urine to drain into an attached stoma bag or fashioning a urinary reservoir or pouch from sections of bowel.

The treatment options for invasive bladder cancer are complex and have many overlapping risks and benefits to the individual patient. For this reason, extensive explanations have not been attempted, as this should be discussed with you on an individual basis at your consultation with the specialist.

CIS, otherwise known as flat bladder cancer, is grouped within the superficial bladder cancers.

This tumour is thought to be the product of an unstable bladder wall lining and the tumour tends to grow into the wall of the bladder rather than into the bladder cavity.

Some 25% of patients will have CIS associated with the more common superficial type of bladder cancer.

Although this is classed as a superficial cancer, there is a high risk (upto 50%) of this type of tumour becoming invasive.

Kidney

Kidney Cancer Q&A

The 2 kidneys are bean shaped organs approximately 12cm in length sitting either side of the spine at the level of the middle back. They have many functions including removal of waste products from the body, production of urine and are important in controlling the body’s water and salt balance. The kidneys are also play an important role in controlling blood pressure.

When the bladder contracts, the urine is expelled via a sphincter mechanism, down the urethra and out of the body. The outer wall of the bladder is formed by a meshwork of muscle fibres arranged in layers.

The inner wall of the bladder has a special lining called transitional epithelium, which is resistant to urine absorption.

Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC) is the most common form of kidney cancer. This arises within the parenchyma (or meat of the kidney) and accounts for up to 3% of new cancers found each year, overall. See also Transitional Cell Carcinoma (TCC).

- Sex: Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC) is twice as common in men as it is in women.

- Age: The peak age for RCC is in your sixties but it can affect all ages.

- Genetics: A family history of RCC can increase your risk of renal cancer, as can specific genetic diseases, such as, Von Hippel Lindau disease.

If your urologist suspects a renal cancer at the time of your consultation, an ultrasound of your kidneys will be arranged.

This test will usually demonstrate any abnormalities of the kidneys. A CT scan of the abdomen will then be arranged which will give more accurate information about the renal cancer.

This will indicate the size of the cancer, the blood vessels supplying the kidney and demonstrate if there is any spread of the cancer out of the kidney. If any further tests are necessary, these will be discussed with you after the CT scan.

Staging of the cancer enables your urologist to decide how extensive the disease is. The special X-ray scans that you have, will enable your urologist to decide on:

- The size of the renal cancer

- Whether the cancer has spread into the large blood vessels, particularly the renal vein

- Whether the fatty tissue or capsule of the kidney has been infiltrated by the cancer

- If the cancer has spread to other organs such as liver, lungs or bone.

Using CT guidance, a small needle can be introduced into the kidney to remove a small sample of the kidney growth. This can be looked at under the microscope to confirm if a renal cancer is present.

The main problem with this particular biopsy is that there is a risk of the renal cancer tracking down the needle path converting a localised cancer to one that can spread.

For this reason the risks and benefits of biopsy of suspicious lesions has to be discussed fully with the patient prior to proceeding.

If the cancer is localised to the kidney, surgical nephrectomy is usually advised. This can be an open nephrectomy or laparoscopic nephrectomy. If a patient has a very small cancer, there are situations where continued observation of the patient may be appropriate over active treatment. If you have poorly functioning kidneys or a single kidney for some reason, you may be advised to have a partial nephrectomy.

If your kidney cancer has spread beyond the kidney to other organs you may be suitable for chemotherapy or immunotherapy, which will be discussed with the urologist and oncologist.

In certain situations, a nephrectomy may be advised in the presence of metastatic disease as occasionally it may give symptomatic relief to the patient and may also have a beneficial effect on the metastatic deposits.

Your urologist will discuss the pros and cons of all of these options with you on an individual basis at your consultation.

If you have had a nephrectomy, you will be seen in the outpatient department some weeks later to discuss the results of the microscopic findings (histopathology).

If all is well you will be followed up on a regular basis with a CT scan of your abdomen, chest X-ray and blood tests.

If everything remains clear after 5 years, you may be discharged from the care of the urologist at this time.

Kidney (Renal) Stones Q&A

A kidney (renal) stone is a mixture of salt or crystals and minerals can that come together and grow as stones in a solution (i.e. urine in this case).

If you imagine adding everyday salt or sugar to water until no more will dissolve, in certain situations, crystals will form due to super-saturation of that solution.

There are no definite answers but it appears that there is a mix of genetic factors (the risk of stones tends to run in families) and environmental factors such as a hot climate or your dietary intake.

Stones tend to occur in the 20-40’s age group and are three times as common in men as compared to women. Other factors include abnormalities of the urinary tract system, recurrent urinary tract infections and some metabolic disorders.

Symptoms can vary greatly ranging from an intermittent dull ache in the middle back associated with general lethargy and fatigue to acute renal colic.

In the latter the patient experiences a sudden onset of pain in the back, abdomen or groin or all of the above. The pain is usually intermittent in nature and can be so severe as to make the patient double over in pain.

Classically, the patient is unable to keep still because of the pain. Feelings of nausea and vomiting may accompany the pain and the patient may notice blood in the urine.

Once there is a suspicion of renal colic, the diagnosis is usually confirmed with a plain CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis. This will delineate the anatomy and confirm the presence of any stones in the urological tract. The majority of stones are either in the kidney or ureter (tube between the kidney and bladder).

Treatment varies according to size and position of the stone within the urinary tract. The size of the stone can range from a small pinhead to the size of a walnut, completely filling the kidney collecting system. Smaller stones may pass spontaneously, however if the stone is too big, intervention may be necessary.

The actual treatment will depend on your clinical history, examination and imaging, usually in the form of X-rays or a CT scan. Nowadays, with the advent of advanced instruments and telescopes, the stone can usually be removed without making any incisions e.g. flexible ureterorenoscopy (FURS).

Other methods of treating stones include percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL), which is a form of keyhole surgery, or dissolution therapy where the stone can be dissolved by changing the acidity of the urine. In some instances, lithotripsy can be used to shatter the stone using a focused, magnified, sound wave.

As a rule of thumb, the smaller the stone, the higher the chance of the stone passing. The small table below illustrates your chances of passing a stone of a particular size as a percentage.

Your surgeon will discuss with you the best options for stone removal at your consultation.

| Stone Size | % Chance | |

| Upper Urinary Tract Stones (kidney and upper ureter) | < 5 mm 5-10 mm | 29-98% 10-50% |

| Lower Urinary Tract Stones (lower ureter and below) | < 5 mm 5-10 mm | 71-98% 25-50% |

Flexible Ureterorenoscopy (FURS) is a preferred treatment for small stones within the kidney using a very thin flexible telescope that can be passed up from the female urethra or end of penis in a man, into the bladder and up the ureter (tube connecting the kidney to the bladder. FURS is offered in the following circumstances:

- Small stones present in the kidney

- Stones resistant to shock wave lithotripsy treatment

- It can also be used to diagnose other abnormalities within the kidney such as unexplained pain or bleeding

The laser is a very fine fibre that can be passed up through the scope to the kidney. Energy from an external power source can break up stones or act as a ‘spot welding’ tool for bleeding points, for example.

FURS is carried out under a general anaesthetic. The first step is to examine the bladder with a telescope and to pass a guidewire and plastic tube up into the ureter (the pipe with connects the kidney to the bladder).

X-ray contrast (dye) fluid is injected up the tube in your ureter. This outlines the kidney system on X-ray and acts as a roadmap for the FURS procedure (see X-ray picture). A small dilating sheath is passed over the guidewire into the ureter and the FURS telescope is then advanced up through the sheath into the kidney. The surgeon can manoeuvre the end of the FURS scope into all parts of the inner kidney using a hand control outside the body to flex the end of the scope as necessary. When the stone is seen, using a video transmitted image to a computer screen, it can be shattered using the laser fibre and power source. Once fragmented, the pieces can be removed using a tiny wire basket, which is passed up through the FURS scope.

Rigid ureteroscopy is a preferred treatment for small stones within the ureter tube, which connects the kidney to the bladder. A thin semi rigid telescope can be passed up from the female urethra or end of penis in a man, into the bladder and up the ureter to the stone. A fine laser fibre can be passed up through the scope to the stone in the ureter. Energy from an external power source can then break up stones and fragments removed using a small wire basket, again passed up the telescope.

It is used in the following circumstances:

- Small stones present in the ureter tube.

- Stones resistant to shock wave lithotripsy treatment.

- It can also be used to diagnose other abnormalities within the ureter such as unexplained pain or bleeding.

Prostate

Prostate Cancer Q&A

The prostate is a walnut sized gland found beneath the bladder, in front of the rectum in men. The urethra passes through the centre of the prostate gland. Ducts coming from the sexual organs (testicles) also enter the prostate gland and join the urethra.

Cancer develops when the cells of the body divide and reproduce in an uncontrolled manner to form a mass of tissue that can invade the surrounding organs and also spread to distant parts of the body (metastases).

Prostate cancer usually develops in the outer part of the gland and can spread locally to the bladder and also to other organs such as liver and commonly to bones. It is not known exactly why prostate cancer occurs, however, it appears to occur as a result of faults in the genes controlling growth and division of the prostate gland cells.

Some known risk factors are as follows:

- Age – Prostate cancer is unusual under the age of 40. Between the ages of 40-60 your risk is about 1 in 100. Between 60-80 years of age, 1 in 8 men may present with prostate cancer. Your lifetime risk is 1 in 6.

- A family history of prostate cancer: If a close relative (brother, father, grandfather or uncle) has had prostate cancer, especially at a young age, your risk is increased compared to the general population.

- Race – Afro-Caribbean men are at higher risk of developing prostate cancer. Japanese men have the lowest risk of developing this type of cancer.

- Diet – If all other risk factors are equal, a high intake of animal and dairy fat can increase your risk of developing prostate cancer. This is based on population studies and is therefore difficult to apply at an individual level.

Initially, prostate cancer may have no symptoms at all. Most men see their GP because of urinary symptoms such as hesitancy, urgency, frequency, nocturia, dribbling, weak stream and incomplete emptying. You will be assessed and investigated if prostate cancer is suspected.

The PSA, Prostate Specific Antigen, is a protein substance produced by the prostate under normal circumstances.

If your PSA is elevated on the blood test, it may indicate that there is a cancer within your prostate. It is important to note that an elevated PSA does NOT diagnose cancer of the prostate.

It merely enables your specialist to decide whether further investigation of the prostate is necessary to look for cancer (for instance, TRUS biopsy).

The normal range for PSA is 0-4.0ng/ml, but this varies according to your age and the reference range used by the pathology laboratory.

Template Guided Biopsy of the Prostate – Biopsy of the prostate will provide tissue from the prostate gland to confirm whether or not there is a prostate cancer. See Template Guided Biopsy of Prostate (link to Q&A section)

An MRI scan of the pelvis -This is a special scan using very strong electromagnets to image the organs within the pelvis including the prostate. This will enable your urologist to check if the cancer has spread out of the prostate.

A bone scan – This test is to see if the prostate cancer has spread to the bones (metastases). A very small amount of radioactive liquid is injected into your arm and some hours later a picture is taken that can detect radioactive “hotspots” in bones that may be affected by prostate cancer.

If the cancer is localised to the prostate, the following options are available:

- Watchful Waiting: In this instance, no specific intervention is offered. It involves monitoring you on a regular basis and intervening if symptoms develop. Some people see this as “no treatment at all”, however, it is based on the fact that your quality of life remains the same as it was before your diagnosis.

It is usually offered to older patients with the understanding that some of the other interventions (such as those listed below) may have more risks and complications compared to the benefit that may be received at the end of such treatment.

Radical Prostatectomy: This is a surgical procedure whereby the prostate gland is removed whole. After removal of the prostate, the urethra and bladder are then rejoined so that you should be able to pass urine normally. This is usually carried out as a robotic-assisted procedure

- External Beam Radiotherapy: This involves shining X-rays on the prostate gland to destroy the cancer cells within the prostate.

- HIFU (High Intensity Frequency Ultrasound) a treatment option that can be used to treat localised prostate cancer.

- Brachytherapy: This is a procedure made popular in the USA, whereby small radioactive needles are implanted into the prostate. This allows a local, high dose of radiation to penetrate the prostate and kill off the cancer cells.

These treatment options have many advantages and disadvantages, which should be discussed with you on an individual basis with your urologist at the time of consultation.

If the cancer has spread, some of the following options are available:

- Watchful Waiting – In this instance, no specific intervention is offered. It involves monitoring you on a regular basis and intervening if symptoms develop. Some people see this as “no treatment at all”, however, it is based on the fact that your quality of life remains the same as it was before your diagnosis.

It is usually offered to older patients with the understanding that some of the other interventions (such as those listed below) may have more risks and complications compared to the benefit that may be received at the end of such treatment.

- External beam radiotherapy – Radiotherapy can be used to treat and control the prostate cancer if it has spread beyond the capsule. This will be discussed between your urologist and oncologists to determine the best approach.

- Hormonal Therapy – Prostate cancer is “driven” by the hormone testosterone. By manipulating your hormone levels, the amount of testosterone within the body can be reduced thereby reducing the tumour size and the overall progression of the tumour may be delayed.

- The anti-testosterone treatments can be in a tablet form or injections that are given monthly or every three months.

- Orchidectomy – This is a surgical option whereby the testicles are removed in order to remove a large source of testosterone from the body. Although it sounds drastic, it is simple to perform and is effective in 70-80% of men.

These treatments are only offered after thorough investigation and discussion with you on an individual basis.

Clinical examination and testing of your PSA levels will be carried out at regular intervals. For example, after radical prostatectomy, your PSA should drop to almost unrecordable levels, ideally to below <0.1. Be aware that different laboratories have different reference ranges and therefore the actually PSA number may be slightly higher than the above.

If after treatment of a localised prostate cancer, your PSA remains at this low level for three years, you can usually assume that the cancer will not come back and that you are cured.

Much research continues into the causes and treatments of prostate cancer. Attempts have been made to identify the possible genes responsible for prostate cancer development and therapies directed at altering the function of these genes may give rise to effective treatments in the future. See links for related sites.

Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy Q&A

Many of the functions of the prostate are unknown. It is known that the prostate produces part of the semen fluid that keeps the sperm healthy and supported prior to ejaculation.

This is part of the normal ageing process in men where the prostate gland increases in size. The prostate grows to its normal size around the time of puberty, however, it then starts to slowly increase in size in the third decade and onwards.

As the prostate gland is somewhat contained by its outer layers, an enlargement of the prostate tends to impinge upon the urethra, narrowing the channel for urine in the process.

This can lead to some of the symptoms of BPH. Around 10% of men in their 40’s have BPH and this figure rises to 50% of men in their 50’s and 90% of men over the age of eighty.

- The male hormone, testosterone, appears to be one main factor that influences prostate enlargement.

- There are a number of specific growth factors within the body that can influence the development of BPH.

- A strong family history of BPH is also relevant.

Patients usually see their GP’s complaining of some or all of the following symptoms: urgency, frequency of urination, nocturia, hesitant or weak stream of urine, dribbling at the end of urination and a feeling of incomplete emptying. Your doctor will go through your history and as part of his examination, perform a rectal examination (DRE).

Examination of the prostate demonstrates whether it is enlarged or not. Your doctor may request a blood test to check your PSA. This can be used as a possible indicator for prostate cancer in some circumstances.

If a diagnosis of BPH is made, the GP will then refer you to a urologist. Your urologist will confirm your symptoms history and repeat the prostate examination to confirm your GP’s findings. Your urologist then may order the following tests:

- Urine flow rate – this will involve you passing urine into a machine that can measure how strong your urine flow is.

- A urine test – this is to check for blood in the urine, infection and also the presence of glucose that may indicate a problem with your sugar control.

- An ultrasound scan (USS) – this is to look at your kidneys and also check if you are retaining urine after you have passed urine. Incomplete emptying of the bladder may confirm the findings of bladder outflow obstruction.

- Flexible cystoscopy – this test uses a small telescope to examine the urethra, prostate and bladder to ensure that there are no other causes for your symptoms.

If your symptoms are not too bothersome and prostate cancer has been excluded, both you and your urologist may decide against actively treating the prostate enlargement (“watchful waiting”).

Drug treatments are available to try and relieve your symptoms. There are two main classes of drugs that are in use:

i) Alpha-blockers. These act by relaxing the smooth muscle of the prostate and bladder neck outlet to improve your urinary flow. Drugs in this group include tamsulosin, alfuzosin, terazosin and doxozacin.

ii) Drugs that stop the production of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) produced from testosterone. The main drug in this group is finasteride. Finasteride takes longer to work and has been shown to be of most benefit in patients with larger prostates.

Your urologist will discuss the side effects of these drugs with you at your consultation.

Operative treatments for BPH include TURIS TURP, Greenlight XPS laser prostatectomy and other minimally invasive therapies, such as Urolift.

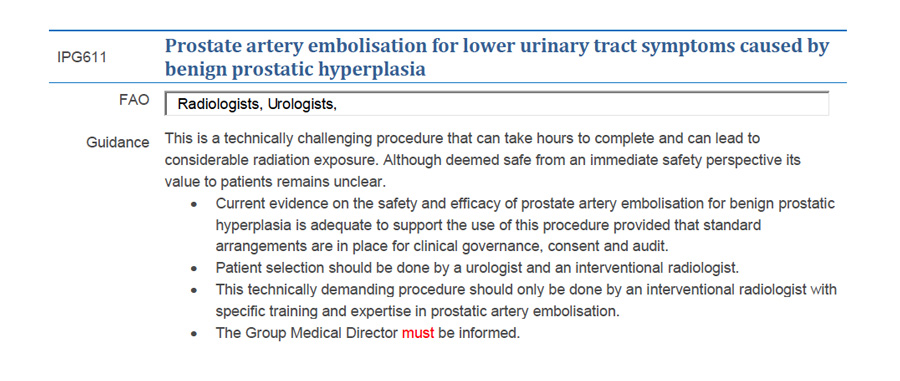

We have had a number of patients requesting information about this procedure. At this current time Essex Urology does not offer this, as it remains a relatively new procedure with less confirmed efficacy when compared with other interventions. The information below summarises some of the issues related to this option, with special attention to the increased radiation exposure required.

Male Genitalia

Hydrocele Q&A

A hydrocele is a collection of fluid in a sac in the scrotum next to the testis (testicle). A smooth protective lining surrounds the normal testis and this makes a small amount of ‘lubricating’ fluid to allow the testes to move freely. Excess fluid normally drains away into the veins in the scrotum. Occasionally, some fluid accumulates as a hydrocele. Hydroceles are normally painless although large hydroceles may cause discomfort because of their size. Walking or sexual activity may become uncomfortable if you have a very large hydrocele.

If the hydrocele causes no symptoms, one option is simply to leave it alone. If it becomes larger or troublesome, you can have the hydrocele operated on to drain the fluid and prevent a further build up of fluid in the future.

The procedure is carried under general or local block regional anaesthesia in the operating theatre. A cut is made into the skin of the scrotum over the hydrocele. The liquid is emptied out. The testicle is examined and if all is well, the inner coverings of the testicle are stitched up to stop the liquid building up again. Finally, the skin is stitched up using dissolvable stitches. A local anaesthetic is usually given just before the general anaesthetic wears off so there is less pain for a few hours after the operation.

For men who have had a general anaesthetic, you will need to arrange for a friend or relative to drive you home and stay with you for the next 24 hours. Try to keep the wound area dry for 48hrs and then bathe as normal. Soap and tap water are quite all right. Salted water is not needed.

You should try and wear the scrotal support for about a week to prevent swelling around the operation site. If bleeding continues, contact us for advice using the numbers below. Avoid sexual activity for a week and no heavy lifting for about two weeks. Driving should be safe after one week if all is well. Check with your insurance company if you have any doubts.

You will be given an appointment to attend the outpatient clinic about 4-6 weeks after surgery. Any questions can be answered at this time.

You will be asked to sign a consent form prior to surgery. The main complications that may occur are as follows:

- Bleeding and pain around the wound site afterwards: this usually settles within 12hrs.

- Infection post-procedure is unusual, but requires antibiotics if persistent.

- Recurrence of hydrocele is again unusual, but can occur, sometimes requiring re-operation.

Circumcision Q&A

Circumcision of males involves removal of the fold of skin (foreskin), which covers the glans penis.

Common indications for this operation include:

- Phimosis – this is when the foreskin cannot be retracted over the glans penis. At age 3 years about 10% of boys are unable to retract the foreskin, but by teenage, the majority of boys should not have a problem.

- Paraphimosis – this is when a tight foreskin is retracted and gets stuck in the retracted position leading to swelling and sometimes pain. This tends to occur in older men, however, can affect any age and should be treated as an emergency. You should seek urgent medical review if this occurs.

- Recurrent balanitis – balanitis is infection of the foreskin causing inflammation and pain around the end of the penis. Antibiotics are usually given in the first instance and circumcision can then be an option once the inflammation has settled.

- Recurrent urinary tract infections – this can be an indication in young boys and should be discussed with your specialist.

The procedure is carried under general or local block regional anaesthesia in the operating theatre. The part of the foreskin to be removed is marked out and the foreskin is gently pulled forward and trimmed away. The edges are closed using dissolvable stitches. A local anaesthetic is usually given just before the general anaesthetic wears off so there is less pain for a few hours after the operation.

For men who have had a general anaesthetic, you will need to arrange for a friend or relative to drive you home and stay with you for the next 24 hours.

Before discharge, your nurse will give you advice about caring for the healing wound, hygiene and bathing. It will be more comfortable to wear loose clothing such as boxer shorts or a dressing gown with no underpants or trousers until the wound has healed. Tight-fitting clothes may rub the wound and make it sore.

It is important to keep the penis clean. The area should be kept dry for 48 hours after the operation. After this, take warm baths or showers once a day. Don’t use bubble bath or scented soaps, as these may irritate your operation site. The penis should be left to dry naturally.

Dissolvable stitches are used so they will not require removal; however the wound may bleed slightly until all the stitches have dissolved.

Children will be able to return to school after 7 to 10 days and resume sports and swimming two or three weeks after the operation provided there is no discomfort or swelling.

Adults should not drive until they can perform an emergency stop without discomfort. This is usually around five days after the operation.

Follow your doctor’s advice about sexual activity. Having an erection will be painful for a few days after the operation. You should not have sexual intercourse until the wound has healed completely. This can take up to about four weeks. If you have sexual intercourse too soon, the wound could re-open and you may need another operation.

You will be given an appointment to attend the outpatient clinic about 4-6 weeks after surgery. Any questions can be answered at this time.

You will be asked to sign a consent form prior to surgery. The main complications that may occur are as follows:

- Bleeding and pain around the penis afterwards – this usually settles within 12hrs.

- Infection post-procedure – rare, but require antibiotics if persistent.

- Meatal stenosis – this is a narrowing of the end of the urethra tube where the urine comes out at the end of the penis. This is a rare complication when the blood supply has been affected to this area of the penis.

- Cosmetic dissatisfaction – this may be due to swelling around the operation site which may not settle. Patients may not be happy with the cosmetic appearance in 2-5% of cases due to this swelling.

Vasectomy

Vasectomy Reversal

Andrology Q&A

Peyronie’s disease is a relatively common benign condition of the penis leading to the formation of fibrous scars or plaques within the erectile tissue. In the early stages Peyronie’s disease can be painful and in the long term it may cause erectile dysfunction and deformity of the penis during erection as the plaque is not elastic and therefore does not stretch as the surrounding normal tissue.

Once the disease is stable, surgery is offered if the erections are poor or the curvature makes sexual intercourse uncomfortable or impossible. Surgery traditionally involves either shortening the longer side of the penis to compensate for the already shortened scarred side (this is known as the Nesbit or Yachia procedure) or lengthening the shorter side of the penis using vascular or artificial grafts (Lue technique).

In patients with associated erectile dysfunction that does not respond to medications, the implantation of a penile prosthesis will correct the deformity and guarantee the rigidity necessary for sexual intercourse.

The last decades have seen a significant improvement in the management of erectile dysfunction, as a variety of medical and surgical solutions are now available to improve the quality of erections.

Erectile dysfunction remains a very complex issue and patients require an expert evaluation to determine the underlying causes of the problem and to identify the most appropriate treatment. Frequently erectile dysfunction is a sign of cardiovascular disease or of hormonal imbalances and therefore the patient needs to be thoroughly investigated.

We offer a wide range of investigations, which will be tailored to each patient’s need. All men should have a detailed consultation and clinical examination at which time a full history will be taken. In patients who do not respond to Viagra, Cialis and Levitra, a test injection might be given to see if this produces an adequate erection. If the patient responds well to injections, then injections can be offered as a definitive form of therapy.

At present, patients can be offered a wide range of treatments depending on the cause of the erectile dysfunction. These range from oral medications (Viagra, Cialis, Levitra) to injections into the corpora of the penis (Caverject). Vacuum devices are a valid alternative to drug therapies in selected patients and may be useful when drugs do not work.

Some rare abnormalities of the penile vasculature can be successfully corrected with revascularization surgery. It is essential therefore for such patients to be assessed by the radiologist and surgeon in order to determine whether they are likely to benefit from this type of surgery.

If none of the medical treatments is successful then patients are offered implantation of a penile prosthesis, which guarantees the rigidity necessary for penetrative sexual intercourse. A variety of penile prostheses are currently available on the market. The simplest are the semi-rigid or malleable prostheses but many men prefer the hydraulic devices, as they can be deflated when the erection is not required and guarantee a better rigidity.

Urethral strictures are narrowings of the urethra and can be congenital or consequence of infection, trauma, pervious catheterization and genital reconstructive surgery.

Patients with a urethral stricture are usually managed with an optical urethrotomy, which involves cutting open the narrow portion of the urethra. However this procedure is associated with recurrence of the stricture in almost all cases and patients will require undergoing repeated urethrotomies over the years. Therefore patients should ideally be offered a urethroplasty, which is a definitive solution and is successful in the majority of cases. This procedure involves the use of oral mucosa to reconstruct the damaged portion of the urethra. The mouth heals very quickly and patients need to keep a catheter for two weeks after the operation. Once the catheter is removed, patients are able to urinate normally.